The Asteroid That May Have Destroyed Sodom, and How Josephus Contributed to the Archaeological Investigation

A recent argument that an asteroid or comet caused the destruction of urban centers in the Jordan Valley over 3600 years ago leads to consideration of the proposed cataclysm as the source of the biblical story of the destruction of Sodom. The plausibility of such an identification depends in part on whether the time and place of the biblical story can be reconciled. On this, Josephus provides some critical information. He also wrestles with the plausibility and meaning of the mass destruction for his skeptical non-Jewish readers. And why was this event intertwined with the story of Abraham?

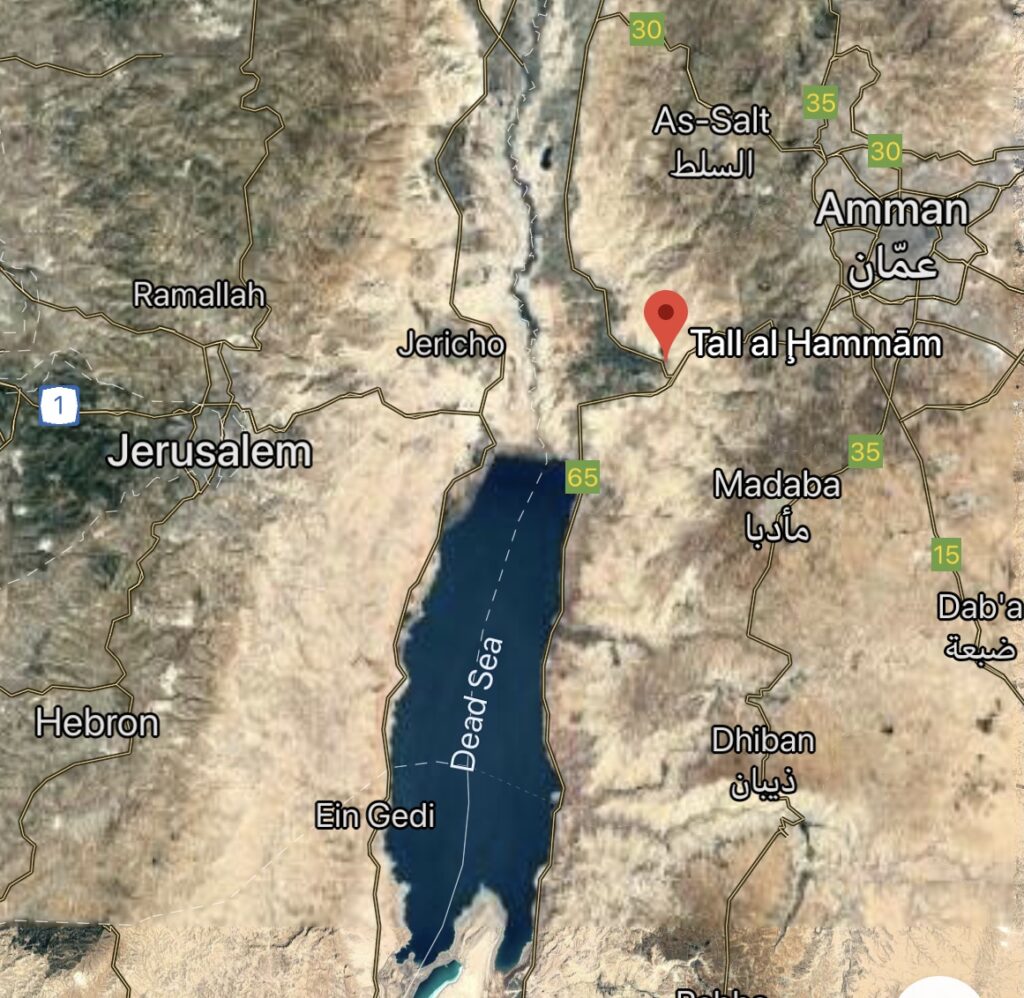

A tremendous explosion occurred over the southern Jordan Valley in about 1650 BCE, destroying a large city at the site of Tall el-Hammam, according to a controversial study by a group of scientists published in Nature Science Reports (Bunch et al., 20 Sep 2021). (A convenient summary is the article by Christopher Moore). The scientists claim that a powerful shock wave of enormous pressure had demolished buildings, fractured grains of sand, and compressed carbon from wood and plants into tiny diamond-like particles. A flash fireball reaching a temperature of 3600 degrees Fahrenheit liquefied bricks, pottery and metal. Metal nuggets embedded across the surface of the debris had iron concentrations consistent with a comet or chondritic asteroid.

As a practical matter, the story of such an event, if it had occurred, should have been long remembered in the region, especially as the devastation was visible to all in the area for centuries. According to archaeologists, destroyed were sixteen cities and towns and over 100 smaller villages in an area fifteen miles wide. A sudden increase in the salt content of the soil, apparently due to water hurled onto land from the Dead Sea, made crops unable to grow, and the region remained abandoned for six hundred years.

A note of caution: this is the conclusion of one group of scientists who have worked together before on speculative cosmic impacts. Other scientists will need to independently verify or refute these conclusions. For a sample of criticism, see for example this article.

The archaeologist Steven Collins proposed the Bible may contain the memory of eyewitness accounts of the destruction at Tall el-Hammam. As he describes in his 2013 book Discovering the City of Sodom, he looked for the remains of Sodom in the plain of the southern Jordan, east of Jericho and north of the Dead Sea, following the description in Genesis 13:1–13. Tall el-Hammam is by far the largest of the many mounds of ruins in the area. In excavating Tall el-Hammam, he reports, he found the remains of a large fortified urban center in a remarkable 5-foot high destruction layer that the group of geologists, geochemists, cosmic-impact specialists and other scientists proposed was evidence of a meteoric atmospheric explosion.

The Bible relates two supposed eyewitness accounts. The one closest to the impact region is attributed to Lot, a former resident of Sodom:

“Then the Lord rained down burning sulfur on Sodom and Gomorrah—from the Lord out of the heavens. Thus he overthrew those cities and the entire plain, destroying all those living in the cities—and also the vegetation in the land.”

Genesis 19:23–24 (NIV translation)

The second possible eyewitness account is attributed to Abraham and is a view from the area of Hebron, looking east:

“Early the next morning Abraham got up…He looked down toward Sodom and Gomorrah, toward all the land of the plain, and he saw dense smoke rising from the land, like smoke from a furnace.”

Genesis 19:27–28 (NIV translation)

Did a cosmic impact, or other catastrophe, indeed occur during the lifetime of the ancestor of the Jews, the Biblical Abraham? The archaeological destruction layer is dated to a narrow range around 1650 BCE. This can be compared with the time when Abraham lived as indicated by the Bible.

However, the surviving manuscripts of the Bible conflict in the time they give for Abraham. The accepted Hebrew version, the Masoretic Text, dates Abraham to around 1800 BCE, far too early for the association with the meteor. But the Greek translation, the Septuagint, does give a date consistent with 1650 BCE. In this conflict, Josephus provides important evidence, for he was writing almost a thousand years before the Masoretic Text was settled, and his version of the story agrees with the Septuagint dating. According to Josephus, and the Bible version he used, Abraham did live at about the time that the meteor destroyed Tall el-Hammam.

Let us look at what Josephus says.

Josephus on the Location of Sodom

The first mention Josephus makes of Sodom is in his Jewish War, written about 80 CE. As he recounts the capture of Jericho in 68 CE by the Roman General Vespasian, Josephus makes a digression to describe the geography in the area of the Dead Sea.

“Adjacent to it [the Dead Sea] is the land of Sodom, in days of old a country blessed in its produce and in the wealth of its various cities, but now all burnt up. It is said that, owing to the impiety of its inhabitants, it was consumed by thunderbolts; and in fact vestiges of the divine fire and faint traces of five cities are still visible.”

War 4.483–484 [Whiston 4.8.4]

Josephus here revises the story for his non-Jewish, Roman audience, who would be skeptical of Biblical miracles, replacing the Biblical “brimstone and fire” with “thunderbolts”. Although Josephus relates it as a local fable, at the same time he cites visible physical evidence in support of the accuracy of the story, the “vestiges of the divine fire and faint traces of five cities”. The implication to the reader is that he has himself seen these things.

The traces of Tall el-Hammam would have been 1700 years old at the time Josephus wrote, and while this is still 1900 years younger than they are now, and so in some ways more visible, it is unlikely that Josephus correctly distinguished the site from any of the other ruins from different eras visible around the Dead Sea. This does not assist in an archaeological identification of the location of Sodom, other than that it was somewhere between Jericho and the Dead Sea.

Josephus returns to the story of Sodom in his Jewish Antiquities, where he retells the Biblical story in detail. He paraphrases Genesis 13 in locating Sodom “in the plain of the river Jordan” (Ant. 1.170 [1.8.3]). This is where Tall el-Hammam is indeed located. Josephus presently describes the destruction of Sodom, extending his account in the War:

“God then hurled his bolt upon the city and along with its inhabitants burnt it to the ground, obliterating the land with a similar conflagration, as I have previously related in my account of the Jewish War. But Lot’s wife, who during the flight was continually turning round towards the city, curious to observe its fate, notwithstanding God’s prohibition of such action, was changed into a pillar of salt: I have seen this pillar which remains to this day.”

Ant. 1.203 [Whiston 1.11.4]

One notes Josephus again attributes the destruction to lightning. As Louis H. Feldman remarks in his Brill commentary, “The notion of brimstone and fire falling from heaven would seem to stretch the reader’s credulity. Josephus here, accordingly, has God hurl his bolt upon the cities in a way reminiscent of Zeus’ punishments”, as seen, for example, in Pindar, Aeschylus and Herodotus (Feldman, Ant. 1.203 n. 627). Notably, Josephus expands on the Biblical account of Lot’s wife by adding to her motivation, which leads to Josephus again citing physical evidence for an otherwise incredible story, the pillar of salt that he himself has seen. Later Rabbinic works also note that the pillar of salt is still present (Feldman, Ant. 1.203 n. 631).

As in Josephus’s time, tourists today are still shown the salt pillars at the southern end of the Dead Sea in connection with the story of Lot’s wife. Archaeologists such as W. F. Albright, in part guided by Josephus and local stories, long sought the remains of Sodom in this region. But Steven Collins, the excavator of Tall el-Hammam, points out this contradicts the Biblical location cited by Josephus above, and there are no Middle Bronze Age remains in the region, and none of any age with the wealth attributed to Sodom (Collins, pp. 103–104).

The hypothesis of a meteoric airburst provides an alternate explanation to the visible salt formations. As described in the Science Reports study, high concentrations of salt were found in the destruction layer, visible even to the naked eye. “For most excavated squares, the newly exposed MB II surface from each day’s archeological excavation produced an obvious white salt crust overnight as humidity leached salt to the surface. Also, we observed…that many pottery sherds and some bones from the destruction layer were encrusted with large salt crystals.” (Bunch et al., p. 48).

The authors of the study hypothesize this layer of salt was the result of water from the Dead Sea forced upon land due to the impact, and that the salinity of the soil made it impossible to grow crops in the area, resulting in the abandonment of a region twenty miles wide for six hundred years after the event. (As noted above, the Bible also states the vegetation of the area was also destroyed.) The “pillar of salt” of Lot’s wife may have come from similar observations shortly after the destruction. Thus it does not need to be a reference to the southern salt formations at all; past archaeologists have been misled to look in the south for this reason (leading some to reject Collins’ original identification of Tall el-Hammam as Sodom, prior to the cosmic impact study).

Another statement by Josephus that has misled archaeologists is that “now that the city of Sodom has disappeared the valley has become a lake, the so-called Asphaltitis [the Dead Sea]” (Ant. 1.174 [1.9.1], apparently based on Gen 14:3 and 14:10). So also the earlier Greek historian Strabo said the lake had “burst its bounds” due to earthquakes and fiery eruptions of sulphur (Strabo, Geography 16.2.44). Both writers allow for the possibility that some ruins are still visible while some are under water.

Thus some archaeologists speculated that the remains of Sodom are at the bottom of the Dead Sea, and there has even been an underwater search for it. But Steven Collins argues this theory is ill-conceived, citing evidence that the level of the Dead Sea in Lot’s time—and in Josephus’s time as well—was the same as it’s current (low) level (Collins, p. 9; 25; 106; 101).

Josephus on the Dating of the Destruction

The Bible associates the destruction of Sodom with the life of Abraham. The biblical dating of Abraham is therefore what needs to be compared to the archaeological Tall el-Hammam destruction date of about 1650 BCE.

Archaeology cannot take biblical accounts at face value. Might it be that Sodom and Abraham are stories from different times, that the Bible writers have joined together? Yet the Bible links them inextricably. It outlines a rich political history for Sodom and its surrounding cities, the wealthy “Cities of the Plain”, before its destruction, and presents Abraham as assisting the cities in their struggle against domination by the kingdom of Elam to the east. After Abraham declines a share of treasure from the king of Sodom, God assures Abraham his reward will be great (Gen 15:1). When three angels visit Abraham, they bring two messages: that he and Sarah will have a son within a year, and that Sodom will be destroyed (Genesis 18). Combining these two events, the birth of their son, Isaac, and the destruction of Sodom, seems to have no motivation, indicating they are only related due to an accident of timing.

Moreover the Bible writers struggle with the morality of the sudden annihilation of thousands of people. Is this the action of a just God? Abraham argues with God on just this point—”Will you sweep away the innocent along with the guilty?”—and two of the visiting angels proceed to Sodom to verify that everyone deserved destruction (Gen 18:22–33, 19:1). This conflict suggests there was a historical necessity to include the Sodom story that overrode the moral difficulties it presented.

Josephus, reflecting Bible interpretation in first-century Jewish thought, is keenly aware of this moral problem. He is more explicit than the Bible that God assured Abraham there would be a reward for his unpaid assistance to Sodom (Ant. 1.183 [1.10.3]). He also is more emphatic that the three angelic visitors had a combined mission: “one had been sent to announce the news of the child and the other two to destroy the Sodomites” (Ant. 1.198 [1.11.2]. (A similar mission assignment of the angels appears in the Talmud, Bava Metzia 86b). Josephus forcefully deals with the problem that his Roman readers, skeptical of the Bible, would see God as having acted unjustly in destroying all of Sodom; Josephus composes a non-Biblical exposition on the sins of Sodom:

“Now about this time the Sodomites, overweeningly proud of their numbers and the extent of their wealth, showed themselves insolent to men and impious to the Divinity, insomuch that they no more remembered the benefits that they had received from him, hated foreigners and declined all intercourse with others.”

Ant. 1.195 [Whiston 1.11.1], Loeb translation

Louis Feldman notes that Rabbinic writings and the Wisdom of Solomon agree with Josephus in identifying the arrogance of wealth as Sodom’s chief sin (Feldman, Ant. 1.194 n. 604; Interpretation, Ch. 6).

Josephus also stresses Abraham’s psychological discomfort with the divine decision:

“On hearing this [the planned destruction] Abraham was grieved for the men of Sodom and arose and made supplication to God, imploring him not to destroy the just and good along with the wicked. To this God answered that not one of the Sodomites was good, for were there but ten such he would remit to all the chastisement for their crimes; so Abraham held his peace.”

Ant. 1.199 [Whiston 1.11.3], Loeb translation

The dissatisfaction that is shown by Josephus and other ancient authors illustrate that the Bible writers were mystified by the cataclysm, but found it necessary to find a justification for it and include it in the Bible due to the association in time of the event with the life of the earliest common ancestors of the Jewish people.

Conflicting Bibles

So a biblical date for for the birth of Isaac produces a biblical estimate for the destruction of Sodom. And the traditional dating of Isaac depends on the length of time between his birth and the Israelite exodus from Egypt.

These time periods and events are archaeologically suspect (this Josephus Blog always takes a scientific perspective). Yet they could have some validity as memories of the Middle to Late Bronze Age.

Faith-based writers who take the biblical time periods as literal have argued against Collins’ identification of Tall el-Hammam as Sodom because the archaeological dating of the site does not fit the strictest interpretation of the received Bible text. (See this argument and Collins’ book, pp. 131–133 and Appendix A.) But that reading is open to debate.

The essential verse for this purpose is Exodus 12:40. But the surviving manuscripts of the Bible disagree on this verse. The Masoretic Text, the standard Hebrew manuscript, has: “Now the length of time the Israelite people lived in Egypt was 430 years.”

This period does not yet include the time from the the birth of Isaac (the destruction of Sodom) to the beginning of the Israelites’ time in Egypt. So some fill the gap by accepting on faith the biblical statements that Isaac was 60 years old when his son Jacob (renamed Israel) was born, and that Jacob/Israel was 130 years old when he went with his children into Egypt. This places the birth of Isaac at least 620 years before the Exodus, when using the Masoretic Text.

But the Greek translation, the Septuagint—whose source may be a Hebrew Bible that differed from the later Masoretic Text—states that 430 years was the length of time “the children of Israel sojourned in Egypt and Canaan“.

In this version, the 430 years includes the period before the entry into Egypt. Taking this figure for the “children of Israel”, that is, Jacob’s children, and applying a more critical approach to ages (e.g., having a first child at age 25) would place the birth of Isaac and destruction of Sodom at 480 years before the Exodus.

Josephus provides essential evidence in the conflict between Bible versions. For his source he used the Septuagint and Hebrew and Aramaic versions that existed in the first century CE. His rendering of Exodus 12:40 is as follows:

“They left Egypt…430 years after the coming of our forefather Abraham to Canaan, Jacob’s migration to Egypt having taken place 215 years later.”

Ant. 2.318 [Whiston 2.15.2], Loeb translation

Thus Josephus assigns 215 years from the time of Abraham’s migration his grandson Jacob’s entry into Egypt, and another 215 years until Jacob’s descendants left Egypt. This would place the time from Isaac’s birth to the Exodus at something less than 430 years.

Josephus’s version may reflect an older Bible than the Masoretic Text. Louis Feldman observes that Rabbinic and Samaritan texts are in reasonable agreement with Josephus (Feldman, Ant. 2.318, n. 848 and 849). (The evidence is not unambiguous: Josephus’s Ant. 2.204 instead gives 400 years as the period of suffering in Egypt, in agreement with Gen 15:13.)

Then to date the destruction of Sodom, one needs a plausible archaeological date for the Exodus from Egypt, assuming the biblical story was indeed inspired by some real migration event. Based on the the mass migrations that occurred with civilization collapse in the Late Bronze Age, the reference on the Merneptah Stele to a people called “Israel”, and the end of the great construction period in Egypt under Ramses (Exodus 1:11), archaeological consensus comes to about 1200 BCE, plus or minus 50 years or so.

Using this estimate, the date for the destruction of Sodom (the year before Isaac’s birth) comes to 1820 BCE if one uses the Masoretic Text, but one obtains 1680 BCE (plus or minus 50 years) from the Septuagint and using common sense lifetimes, and something a little later using Josephus in Ant. 2.318.

The Science Reports study of the cosmic explosion by Bunch et al. uses radiocarbon dating of broken plaster, limestone spherules, carbonized wood, grains and seeds, charred bone and other organic materials in the Tall el-Hammam debris layer to arrive at a date of 1686–1632 BCE with a 68% confidence interval. The authors then rounded to allow for uncertainties to date the cataclysm to 1650 BCE plus or minus 50 years (pp. 7–8). This was consistent with Collins’ estimate based on pottery styles.

This dating of the meteoric destruction is thus in rather surprising agreement with a reasonable application of the bible-based chronology in Josephus Ant. 2.318 and the Septuagint. Of course, the source of the latter numbers is not known, so their historical validity cannot be estimated. Also, the archaeological uncertainties allow for a range of 350 to 550 years between an Exodus-like event and the cosmic impact. But if the biblical numbers have any value as a Bronze Age memory, they provide support for identifying the destruction of Tall el-Hammam as the source for the biblical story of the destruction of the five Cities of the Plain—Sodom, Gomorrah, Admah, Zeboyim, and Bela.

The Morality of Meteors

A Bible-based belief that God punished a wicked Sodom does not need an explanation of the mechanism of destruction, but it is not necessarily contradicted by the cosmic impact hypothesis: one can choose to believe that God used an asteroid or comet as the instrument of punishment.

In contrast, a scientific perspective takes the meteoric collision as a natural event. The path of the asteroid had no moral intention behind it. Rather, in this view, the Bible story may reflect how the people in the region adjacent to the catastrophe created a cosmic morality story to explain why their neighbors were annihilated—and why they themselves were not.

Josephus strove to span these two perspectives; his goal was to justify his Jewish religion to his scientifically-inclined Greco-Roman audience. He does say that Abraham was given warning of the divine plan for Sodom. But first Josephus presents Abraham as a rational scientist, one who instructed people in mathematics and astronomy. It is from observing the motions of the celestial bodies that Abraham derived the concept of one God that controlled nature. For this, Josephus may have been partly drawing on Gen 15:3. (Ant. 1.154–157, 1.166–168. Other ancient writers describe Abraham similarly; Feldman, n. 501, 538.)

In the Bible, God walks with Abraham one night and tells him, “Look towards heaven and count the stars, if you are able to count them.” And adds, “So shall your offspring be.” (Gen 15:3)

From the starry sky, disaster will fall on others.

The night before the destruction, God again walks with Abraham. He has decided of Abraham, “I have singled him out, that he may instruct his children and his posterity to keep the way of the Lord by doing what is just and right.” (Gen 18:19).

Taking a psychological perspective, a sudden catastrophe can have shocked some people of the time into believing they had indeed been “singled out” to survive. In this view, the Abrahamic faiths may owe to this event a portion of their conviction that survival depends on behaving with empathy and justice toward all.

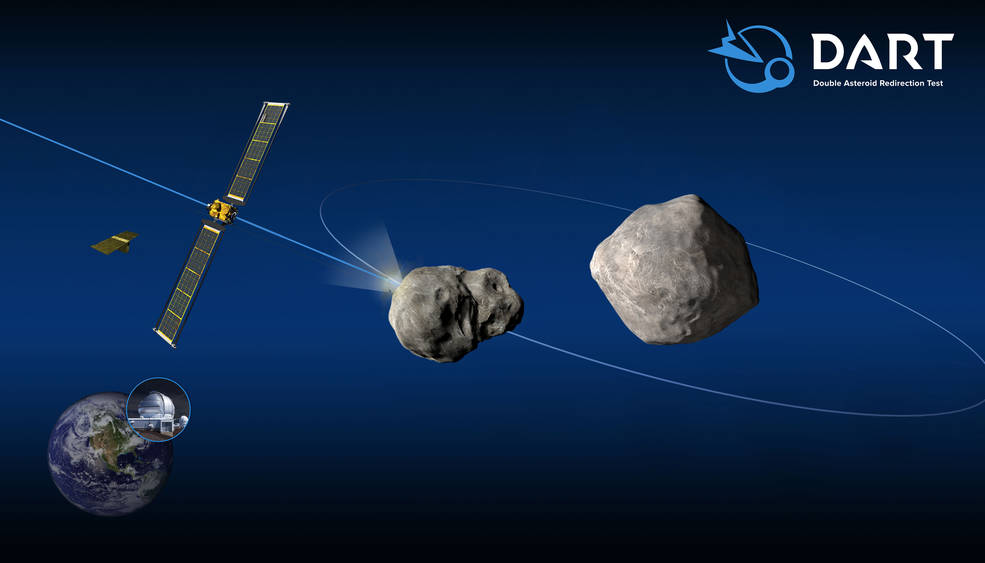

But this would not be a mistake. Modern science may owe something to this moral interpretation of the catastrophe. Perhaps it can be said the sin of Sodom was representative of that of all humanity—the sin of not understanding essential facts about the universe, of not finding the means to discover that there are great powers that have the ability to destroy life on earth in an instant.

A cooperative society that develops, as in the Abraham story, with the obligation to do “what is just and right” to keep from destruction, is a prerequisite for the preservation of collected wisdom and the building of knowledge over time. Through millions of tiny acts of empathy and decency over a time span of millennia, this civilization produced Galileo Galilei, Isaac Newton, Albert Einstein (a presumed descendant of Abraham’s) and many, many others, who together developed the science of celestial mechanics that has given us the ability to prevent a catastrophic cosmic impact from ever happening again.

A few days ago, NASA launched a spacecraft in its DART mission to target Dimorphos, a small rock orbiting the asteroid Didymos, as a test of humanity’s ability to deflect an asteroid away from a collision course with Earth.

It seems worthwhile to reflect on whether the building of a society that can develop science and produce this achievement owes something to the ancient belief that humanity must continually engage in doing what is right and just in order to avoid destruction.

References

Bunch, T.E., LeCompte, M.A., Adedeji, A.V. et al. “A Tunguska sized airburst destroyed Tall el-Hammam a Middle Bronze Age city in the Jordan Valley near the Dead Sea.” Sci Rep 11, 18632 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-97778-3

Moore, Christopher R. “A Giant Space Rock Demolished an Ancient Middle-Eastern City and Eveyone In It, Possibly Inspiring the Biblical Story of Sodom.” The Conversation, Sep 20 2021.

Collins, Steven and Latayne C. Scott. Discovering the City of Sodom. (Howard Books, April 2013).

Feldman , Louis H. Judean Antiquities 1-4. Vol. 3 of Flavius Josephus: Translation and Commentary. Edited by Steve Mason (Brill, 2000). Open access at the Project on Ancient Cultural Engagement.

Feldman, Louis H. Josephus’ Interpretation of the Bible (Univ. of California, 1999).

Josephus. Translated by Henry St. J. Thackeray et al. 10 vols. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1926-1965.